In this latest post on language ideologies in the wild, I’ll be discussing the popular app Duolingo, which describes itself as “The world’s best way to learn a language”. As usual, I’ll be discussing the language ideologies behind the assumptions this app makes about languages and language learning, and the ways these ideologies contribute to social inequities. To be clear, as with the rest of the posts in this series, I do not think this is intentional on Duolingo’s part, but it is the natural consequence of not being aware of language ideologies. It’s also true that you could level many of the critiques I’m making of Duolingo at introductory language classes, but Duolingo is the app I’ve heard uncritically recommended on multiple podcasts recently (and I’m not sure I’ve ever heard a language class recommended!).

So, what are some examples of the language ideologies upheld by Duolingo?

They primarily center around two ideologies I’ve discussed before, as they are so socially dominant: the nation-state ideology and the language as a decontextualized object ideology. The nation-state ideology assumes that language and national boundaries are distinct and mutually reinforcing, and was central to the creation of European nationalism and “national” languages. It either ignores, others, or actively excludes language users within these national boundaries whose language use doesn’t always conform to the national standard, generally because they do not belong to a dominant social group. This also delegitimizes the linguistic practices of multilingual speakers, who are the majority of the world’s population.

The language as a decontextualized object ideology takes language out of its social context, presenting it as an object that can be analyzed and understood independently of this social context. Conceiving of language as a decontextualized object is key to the ideology of standardization, where certain ways of using language are seen as “standard” and others as “non-standard” or even “incorrect”. Decontextualization obscures the fact that these descriptions of language are judgements of the social groups that use these forms, not the linguistic forms themselves. “Standard” language forms are simply the language of the socially dominant, as these groups are the ones with the power to standardize the language based on their own linguistic practices. In turn, this allows for language to be a proxy for other types of discrimination, such as racism and classism, including in situations where people are actively trying to work against these social inequities. The nation-state ideology and the ideology of language as a decontextualized object support each other in the creation of standardized national languages. They were also central to the colonial project, where linguists would identify languages, match them to particular ethnic groups, and then use their analysis of grammatical elements of the language to support ranking these languages (and their speakers) as inferior to European ones. So, while both of these ideologies are socially dominant in many places, they are far from benign, and they continue to reinforce social inequities.

So, what are some examples of these language ideologies in Duolingo?

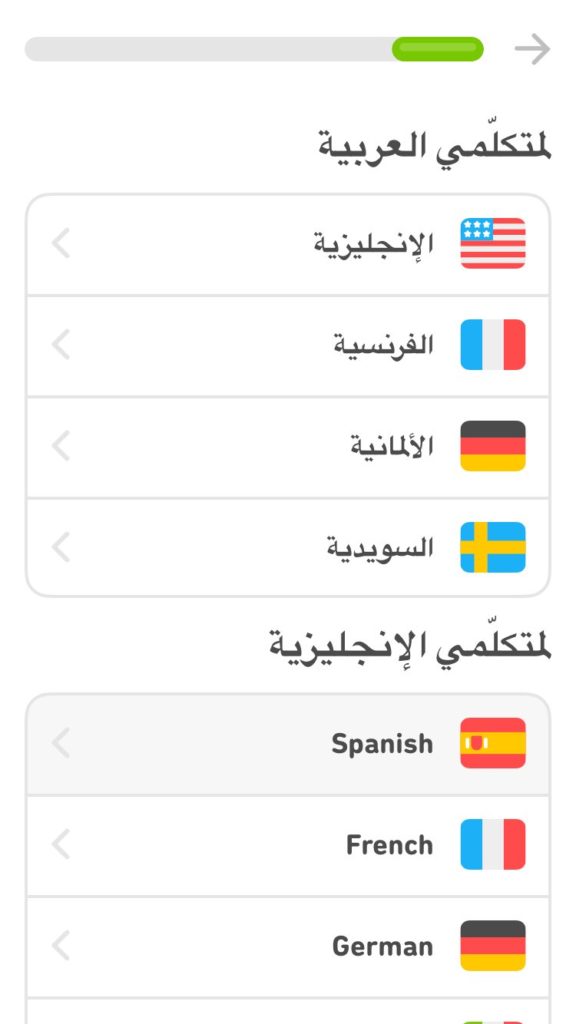

We can start with the use of flags to represent languages, a common practice and hallmark of the nation-state language ideology. It’s especially problematic to represent major world languages, such as English, French, and Spanish, with the flag of just one dominant country (often the original colonial power, or in the case of English, the US). Even smaller languages, such as Scottish Gaelic or Navajo, are spoken across national borders (e.g. Cape Breton or outwith the Navajo Nation), and it is important to recognize this. Arabic notably does use the flag of the Arab League rather than a particular nation, but even so, there are Arabic speakers outside of these countries (and non-Arabic speakers within them).

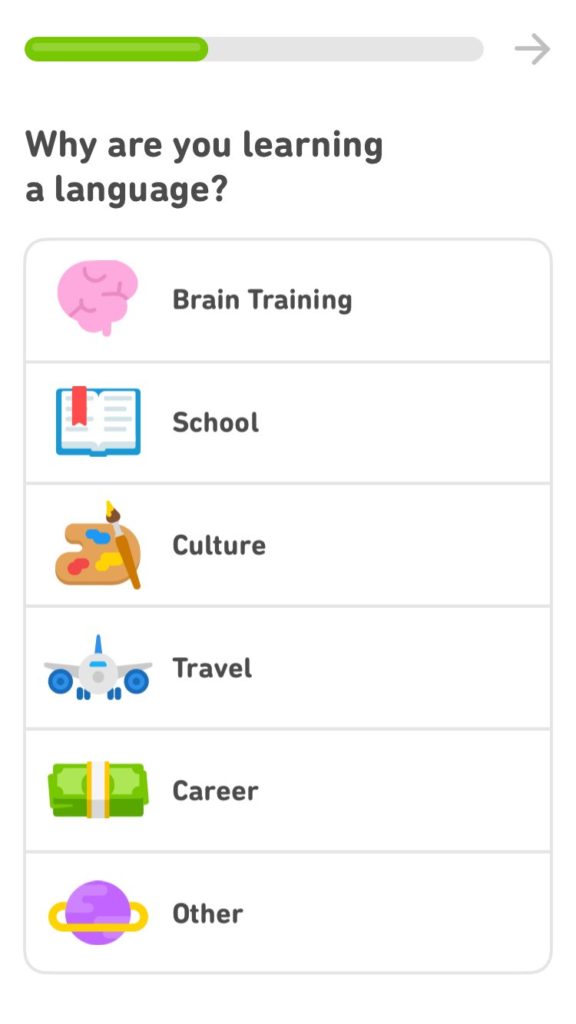

Next, we can look at the assumptions underlying why Duolingo thinks people would want to learn a language: brain training, school, culture, travel, career, and other.

Thinking of language as brain training, as I’ve written before, requires viewing language as a decontextualized object, and pieces of language (words, sentences, etc.) as interchangeable across languages, rather than tied to specific social settings. Language learning for “school” and “career” emphasize professional aspirations over personal, social relations (though obviously these are necessary in both settings!). “Travel” could be a personal activity, but this goes back to the idea of crossing national borders to learn language, and ignores the fact that we are already living in multilingual communities, whether we recognize this or not. “Culture” is so vague that I’m not sure what this really means, but what it makes me think of (especially with the icon of an easel) is the Grand Tour, where elite Britons and Americans would travel to Europe as part of a “finishing” experience to engage with high culture, including language learning. A primary purpose of this experience was to cement their high social standing upon their return, and both study abroad and language learning continue to be a way for those with high social standing to uphold this status (in contrast, the language skills and geographic mobility of immigrants of lower socio-economic status are rarely so valued).

Notably absent from this list are social relationships, such as those with friends, or family, or participants in a favorite activity (say music, dance, sports, or even school/work!) that might encourage one to pursue language learning. Emigration or moving to a different multilingual community is also absent. While “Other” is of course an option, what does it say when we mark personal relationships as Other?

Then, there are the actual activities in Duolingo, which based on my experimentation with Spanish and Scottish Gaelic involve translating sentences related to a general theme (but not to each other) in a variety of ways. They also appear to be mostly the same across languages, with some notable exceptions (“guga” in the food section for Scottish Gaelic, but if I didn’t already know what this was, I’m not sure knowing the translation “salted gannet” would help, and the cultural context is also obscured). This translation of interchangeable sentences supports the decontextualization of language, and this is further enhanced by the fact that the same cast of characters cheers you on no matter which language you are studying. It’s worth noting that this cast of characters is diverse (including for example a woman wearing a hijab), which is one reason I don’t think Duolingo is intentionally trying to uphold social inequities. It’s also true that having different casts of characters could be highly problematic, for example if all the English speakers were White, or the Hijabi woman was only used for Arabic. At the same time, Duolingo is clearly recording real people saying these sentences, so there seems like a lost opportunity to represent the diverse speakers of these languages.

This also appears in Duolingo’s choice to offer different accents as an upsell. While I understand that they are a business that needs to make money, the choice to have multiple accents as a bonus, rather than an essential part, once more upholds the nation-state ideology. (And is there really one Latin American accent for Spanish!?)

Finally, we can see these ideologies in some of the quotes that appear when Duolingo is loading. One says something like:

You can learn a language in just 15 minutes a day, but what would 15 minutes of social media do?”.

This assumes that “social media use” is separate from “language learning” but in fact social media is a highly engaging way in which people use language! Spending 15 minutes a day perusing social media in the language you are learning is a great way to learn in a more socially connected way!

Then, there are quotes like this one:

More Americans are learning a language on Duolingo than in the U.S. public school system.

This is probably true, but it’s reflective of the fact that U.S. society values language learning as a “nice to have” add-on for elite students, not the appeal of Duolingo. Is this really something exciting?

Or this one:

34 hours on Duolingo teaches as much as one semester of a university language class.

Based on contact hours? Based on translating sentences? Leaving aside the fact that university language classes vary widely in what they teach, this goes back to the ideology of decontextualization, in the idea that language learning can be objectively measured and compared. Now certainly you can choose measures and compare them, but the more interesting question is what does your choice of measures say about your language ideologies?

Or:

In Sweden, the most popular language on Duolingo is Swedish (mostly by refugees).

I wonder, do we hear those Swedish-speaking refugees voices in Swedish Duolingo?

In short, while Duolingo may be a fun game to play, and you may learn some sentences in another language from it, it also upholds language ideologies that contribute to (and were originally designed to reinforce) social inequities. As noted earlier, I don’t think this is the goal of Duolingo users or the company itself, but it is a consequence of ignoring of the language ideologies that inform our choices about language learning. Being aware of these language ideologies is an important first step, but I’ll also close with some recommendations for Duolingo users (if you like the game) and the company itself (in case they happen across this post!).

Recommendations for Duolingo users:

- Think about what social contexts you are planning to use this language in (or if you’re not planning to engage with speakers of the language, why is this?). How will you participate in these contexts?

- Engage with contextualized language–this could be conversations with speakers of the language, but it also includes media, including YouTube or social media. Make sure this contextualized language includes a a wide variety of speakers, including those who speak “non-standard” varieties, or mix languages, or are socially marginalized (you don’t need to learn the “standard” form first, you do need to be aware of the social meanings)

- Remember many of these contexts will be multilingual, and you can still learn in them (for example, you don’t need to have a conversation only in Spanish to improve your Spanish, this is just a monolingual language ideology)

Recommendations for Duolingo:

- Think about the language ideologies underlying the quotes and activities you use, and their consequences in terms of social inequities

- Include more accents, sociolinguistic information, and real speakers (from diverse backgrounds, including multilingual ones) as a feature from the beginning, not a “Plus” feature (upsell something else!)

- Don’t use flags to represent languages (and really think about whether an icon of any sort can represent all of the people who use a language)

- Include more contextualized, culturally specific language (with explanations too!).

- Include explicit information about language ideologies and linguistic hierarchies, rather than assuming dominant ones

- Include personal relationships as a key part of language learning and use

Unlike Duolingo, I don’t actually think there is a “best” way to learn a language, but no matter what methods we choose, it’s crucial to be aware of the language ideologies informing our conceptions of language. Are the ones we’re upholding really the ones we want to be perpetuating?

Comments

2 responses to “Language Ideologies in the Wild: Duolingo”

Enjoyed the read

Very interesting

Thanks

I’d love to hear what you have to say about 7Speaking.com and about learning language with a platform like this rather than in a group/individually face to face with a real live teacher 🙂

Hi, I don’t know much about 7speaking.com, but my concerns are more with the ideologies behind how language learning is presented rather than the medium in which it is learned (app, face to face, online, etc.). The 7speaking.com website gives me pause because it compares itself to "face to face lessons" (hardly a homogenous activity) and it seems very focused on test scores (but this may be what matters to its audience).