This is a question I get frequently when I advocate for a multidialectal approach to learning Arabic. The short answer is no.

The longer answer is also no, but with a much lengthier explanation, which I thought I’d give in this post. In general, there are two types of people who ask this question. The first category is those who want to discredit dialect teaching completely (every village has its own dialect, how can you possibly choose, MSA is the answer). The second category is people who find the idea appealing, but the process confusing (does this mean teaching every word in major dialect groups? Isn’t that a lot to ask of students? How do you do this all in class?) This post is aimed at that second category, as those coming from the first have an ideological perspective I will always be at odds with.

What is a multidialectal approach?

So, what do I mean by a multidialectal approach? As Sonia Shiri and I describe in a recent article, this is a response to the MSA plus one dialect approach, that is itself a response to the MSA only approach favored when I started learning Arabic. In the MSA (Modern Standard Arabic) only approach, only MSA is taught with the idea that it is the shared, standard variety so you can use it anywhere. This is sort of true, in the sense that you can speak MSA and be understood almost anywhere. However, the challenge is that MSA is not sociolinguistically appropriate in most everyday contexts, so if you only know MSA, you are unlikely to be able to understand the interactions around you, and engage in a sociolinguistically appropriate manner.

A key piece of this confusion is the use of the term “standard”–in many languages, there are people who speak the “standard” variety in their everyday lives (e.g. the socially powerful in that society). In Arabic-speaking settings, this is simply not the case. While there are those speakers who get interviewed on the media for the unusual practice of speaking MSA to their children, Arabic speakers generally grow up learning to navigate a continuum between local dialects and MSA influenced by social factors.

As a result of student and teacher frustration with an approach that limits students’ abilities to engage socially, there has been more incorporation of dialects into classroom and textbooks, generally following the “MSA plus one dialect” approach, where students learn MSA plus one national dialect (generally a prestigious urban form), either in two separate classes, or following an integrated approach (both varieties in one class). While this is certainly an improvement over the MSA only approach, it is also firmly rooted in monolingual language ideologies (one dialect=one nation) and this leads to all sorts of logistical challenges: what if the teachers in a program are from different dialect backgrounds? What if a heritage student is from a different dialect background? What if students want to study in different countries? What dialect do we choose? In some contexts (such as teaching Arabic in a specific Arab city with a dominant dialect, e.g. Cairo) this may be easier to choose, assuming that students are looking to engage with the people immediately around them. In others, the seemingly impossible nature of this choice leads to a return to the MSA only approach.

A multidialectal approach avoids this issue viewing “Arabic” as a group of linguistic resources employed in various ways according to a negotiation between the social context and learner choice and/or knowledge. So what does this look like in practice? Below, I’ll discuss some principles of the multidialectal approach, my response to common objections, and also ongoing challenges in the classroom

Principles of a multidialectal approach

Distinguishing between receptive and productive abilities

For the most part, research on the mutual intelligibility of Arabic dialects indicates a high level of comprehensibility, that grows even higher when speakers are interacting with each other, and thus making linguistic accommodations to communicate. While speakers of less socially prestigious dialects certainly have to shift their speech more, the mutual comprehensibility is largely a result of the receptive abilities of the speakers, and their lifelong practice of understanding dialects other than their own. In my opinion, this distinction between receptive and productive skills is something that deserves a lot more attention in the Arabic classroom–we don’t need to expect students to produce every single dialect, but if their goal is interacting with Arabic speakers from a wide variety of backgrounds (and it often is!) we do need to work on our ability to understand multiple varieties. In terms of actual classroom practice, this may mean watching videos of similar interactions in multiple dialects, to help learners develop this ability, while letting them choose the variety they want to use when they engage in the interaction themselves.

Developing meta-linguistic awareness

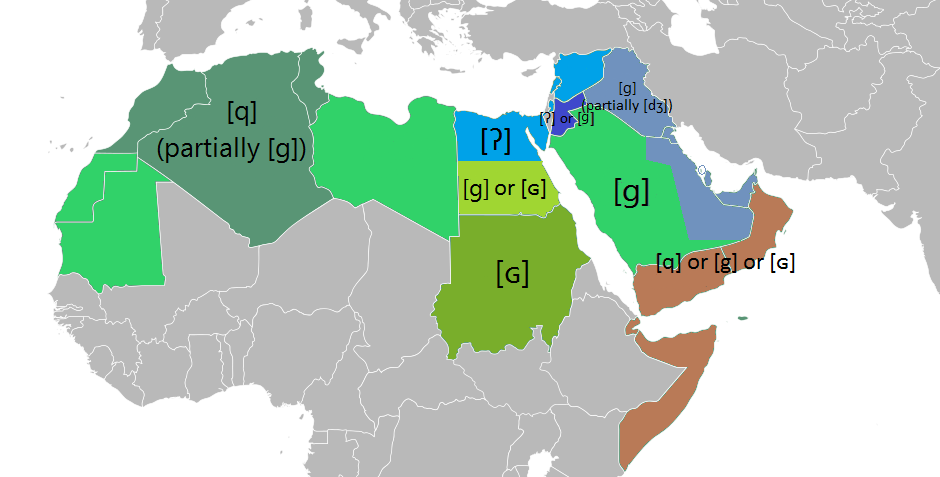

In order to develop these receptive and productive abilities, we also need to help students develop meta-lingusitic awareness. While this is a lifelong skill, it’s important to train from the beginning. Yes, there is a lot of variation in Arabic, but it’s not random, and practicing with highly salient and expected features from the beginning (e.g. q pronunciations, lexical variations for syntactic features like بتاع حق etc.) can be very beneficial. The key word here is practice, simply telling students about the variation isn’t enough, they need to practice understanding it.

Focus on social actions, rather linguistic varieties

One way of avoiding the question of “which variety to use” is to actually look at what varieties people do use, and what this says about their social context. For example, finding examples of greetings, or family descriptions without worrying about the variety, and then analyzing these examples to develop meta-linguistic awareness (to understand a similar variety in the future) along with the language to actually do this social function (right now, in class). This is the basis of the clips on the We Can Learn Arabic site, where we do use multiple varieties in class, and discuss the variations in them and their social meanings.

Common Objections to a Multidialectal Approach

The most common objections I hear to this approach (and teaching dialects generally) are “it’s too confusing for students”, “what if they mix dialects in funny ways”, and “what if the teacher doesn’t understand everything in a dialect”. From my perspective, these are all ideological differences. They are rooted in monolingual language ideologies, where it’s assumed that languages are separate, bounded entities learned sequentially and fully, a model that fails to describe the linguistic practices of most of (all of?) the world. The first objection is also tied to formal perspectives on language learning where lexical and grammatical elements are the basis of language, and social elements an additional, separate layer. Yet if we take the perspective that language is inseparable from social context, we can’t abstract this social layer away. So might students be confused? Yes, almost certainly. But would we not teach essential grammatical elements, like broken plurals, or the iDaafa, because they confuse students (and they do!)? Of course not, so why would we avoid social elements because they might be confusing?

In terms of “mixing dialects in funny ways”, yes, students will do this. They will also conjugate verbs in ways that sound funny to us, but do we use this as a reason not to teach verb conjugations? No, we just help them sort it out over time. We might also want to question who gets to arbitrate what sounds “funny”–while certainly language learners make mistakes due to a lack of knowledge, having analyzed hundreds of online videos for the We Can Learn Arabic site and class, I feel quite confident that there is all kinds of dialect mixing in use in real life that might sounds “funny” to Arabic teachers used to separating linguistic varieties. In fact, it was analyzing all of these videos that led me towards embracing a multidialectal approach–if this is what people do, who am I (or any teacher) to regulate it?

It’s true that the teacher might not understand everything in a particular dialect or video, and this is certainly true for me. It also has an easy solution–look it up or ask for help! In fact, I might argue that modeling how you do this is particularly useful for students, as it provides them with the ability to do the same thing themselves. Even better, you get to learn new things, and what teacher doesn’t like that?

Ongoing Challenges of a Multidialectal Approach

While I think the objections mentioned above are spurious, I also don’t want to suggest that a multidialectal approach is without challenges, and so I wanted to also discuss two of these that I have struggled with in particular.

Language Ideologies:

Have you noticed a common thread yet? This is why an awareness of language ideologies is so, so important! Because monolingual ideologies are dominant in our society, this is what students (and teachers) come to class with in terms of their expectations about language. So, when they hear “multidialectal” they often assume “equal productive capacity in all dialects” and that sounds overwhelming (because it would be!). They also assume it’s better to start with one variety (be it MSA or a particular dialect) and “master” that one before starting on a new one, following the monolingual model. We try to address these ideologies head on, and help students think about them, but it’s a challenge to fit this into a language class. And yet, especially in an environment where so little is expected in terms of language learning, I sometimes wonder what is more important–learning a few more phrases in Arabic? Or learning to see, question and resist oppressive language ideologies?

Meta-Linguistic Awareness:

Having a very basic linguistics background (like understanding where sounds are made in your mouth, different syntactic structures, what morphemes are) makes teaching meta-linguistic awareness much, much easier. Alas, unless a student is a Linguistics major or minor, they are unlikely to have studied this (all the more reason to teach Linguistics in primary and secondary education levels!). Helping students develop this awareness, without turning the session into a Linguistics class, is also a challenge. Although, as with linguistic ideologies, I often wonder what is more useful in the long term–a little more Arabic, or meta-linguistic knowledge that can be applied to any language, including ones we already know?

So, that is my very long answer to the question “Does a multidialectal approach mean teaching all of the dialects?” If you have tried a multidialectal approach, or would like to try it, I’d love to hear how it’s going, or what challenges you’re facing. Let me know in the comments or via email!

Leave a Reply