At the recent conference for the American Association of Applied Linguistics, I organized a colloquium with Rhia Moreno Kilpatrick called Disrupting the Whiteness of U.S. Study Abroad. The other presenters in the colloquium were Uju Anya and Wenhao Diao, whose work I also recommend checking out, especially as Uju’s amazing book Racialized Identities in Second Language Learning: Speaking Blackness in Brazil won the AAAL first book award this year! For some numerical background, according to the Open Doors report, 71% of U.S. Study abroad students are white.

This post is a summary of part of my talk where I used photos on a program website to demonstrate how even when we take real steps (such as financial support) to promote and support including underrepresented groups in study abroad, we often still do it in a way that doesn’t really challenge what I called the “default whiteness” of study abroad. That is, we focus on trying to increase the numbers of students of color studying abroad, but don’t really think about some of the problematic ways in which we represent study abroad. To explain what I mean, I’ll look at two pages of a program website.

In critiquing these pages, I want to make it clear that while I chose this website for my example, this is not so much a critique of this specific program (which I have worked with for a faculty-led study abroad in the past), but of U.S. study abroad generally (which I am also a part of as a researcher, practitioner, and former study abroad student). The problems I describe are readily apparent in most study abroad websites I look at, even to a larger degree than the pages I’m critiquing here. In fact, I chose these particular pages because this program is in fact making some concerted efforts to include underrepresented groups in study abroad.

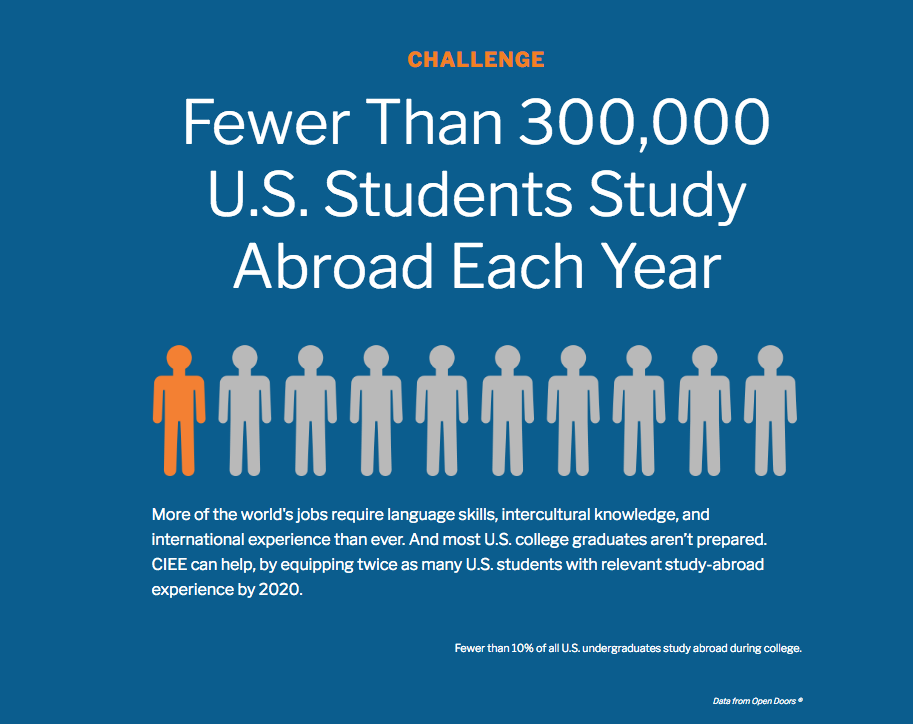

So, what are the problems? We’ll start with this page, which is focused on increasing access to study abroad. As page content changes (hopefully for the better), I’m putting screenshots of the page as it is when I’m currently writing this (March 2019).

The page opens with a “challenge”, explaining “More of the world’s jobs require language skills, intercultural knowledge, and international experience than ever. And most U.S. college graduates aren’t prepared.” It then offers increasing study abroad as a solution to this problem. While fully support increasing the numbers of students studying abroad, presenting study abroad as the only solution to getting “language skills, intercultural knowledge, and international experience” is highly problematic, as it erases the language skills and intercultural knowledge students gain within the United States, for example by being raised in multilingual communities, or needing to accommodate to dominant white middle class cultures that differ from home or community ones. International experience is also something that students could have if they emigrated as children, or live in border areas. Racially minoritized students are almost certain to fall into one or more of these categories, and yet the skills they develop are not recognized as relevant to study abroad.

Next, the page talks about solutions, and how to address the “three C’s”—Cost, Curriculum, and Culture. Again, cost is a major barrier, especially as we know there is a racial wealth gap. Curriculum is also important, and we know that including more short-term programs in a variety of disciplines has helped more students study abroad. So, addressing these problems is essential. However, I want to focus a little more closely on the “culture” aspect of study abroad, where the website presents the solution as “nurture acceptance, approachability, value, and adventure in the study-abroad landscape.” Nowhere is race mentioned, even though we know racially minoritized students are underrepresented in study abroad, and the “culture” of study abroad is predominantly white and (upper) middle class. While racially minoritized students are not the only groups underrepresented in study abroad, not mentioning race perpetuates a “colorblind” ideology that obscures the real structural problems we face in overcoming racism.

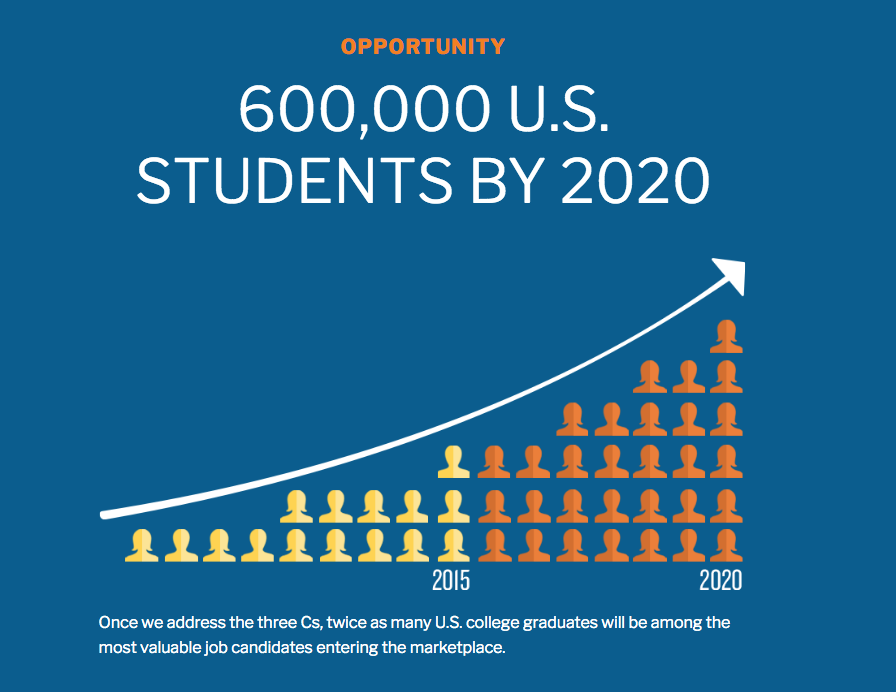

Then, the website moves on to “opportunity” explaining that by increasing study abroad, we can make more U.S. students valuable job candidates. This raises other concerns I won’t go into in this post, such as the neoliberal connection with jobs and “value”, and the colonial perspective in emphasizing only this value to U.S. students and using words like “adventure” to describe study abroad, but perhaps in other posts!

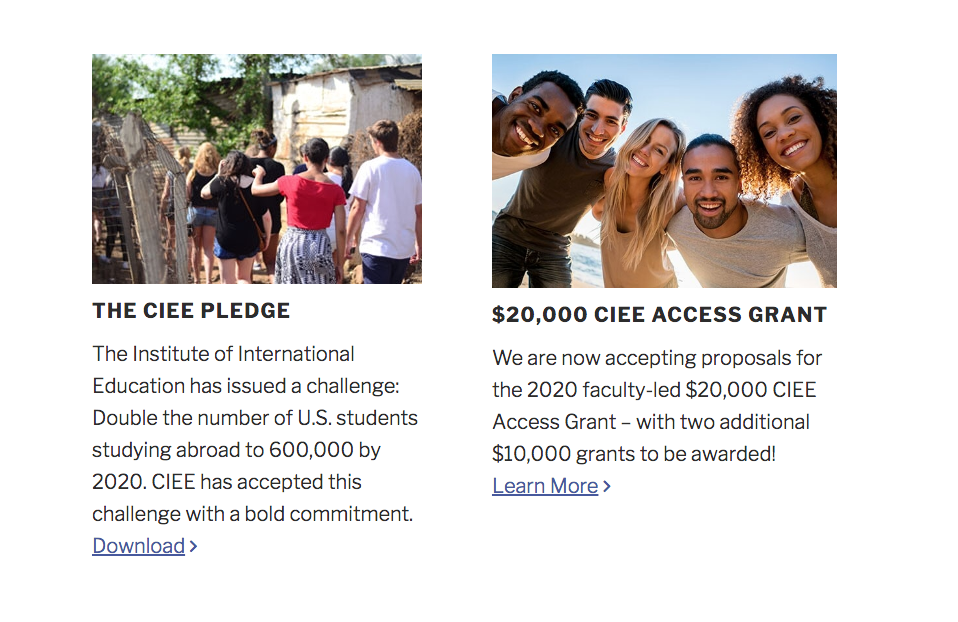

What I’d like to focus on next though is the pictures at the bottom of the page, above “The CIEE Pledge” and the “$20,000 CIEE Access Grant”. The students above the former, presumably already abroad, appear to be mostly white. In contrast, more of the students in the latter appear to be students of color. Now, race is a social construct, so I want to make it clear that judging someone’s race from photos is a problematic practice, and certainly influenced by my own racial position (white). However, I think it is also problematic to juxtapose photos of students abroad and students who needed extra access to study abroad where the former appear mostly white and the latter mostly to be students of color. While it is true that many study abroad websites don’t represent students of color at all, and this is even worse, I think we also need to be careful how and where we represent students of color in our study abroad websites to avoid reproducing deficit perspectives that dominate in education settings.

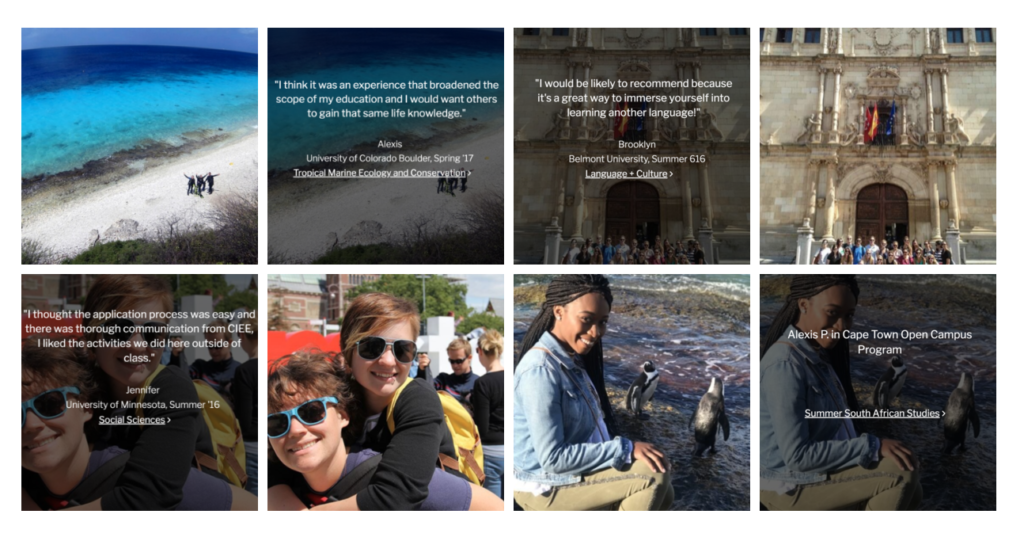

This issue is even more apparent on the next page, which is the main college study abroad page for the organization. If we scroll past the tourism photos (another subject for another post!) till we get to people, the following four photos appear in a gallery you can scroll through

If you hover over the photo, there is a testimonial quote from the student, and the program (which I’ve just screenshotted as separate pictures). In three of the four photos, there are pairs or groups of students who present (to me) as white, with no specific location given for their studies. The fourth picture is of a student who presents (to me) as black, alone with some penguins, and listed as studying in South Africa (with no personal quote). Again, it is important to represent students of color in photos of study abroad, so this is an improvement over no representation at all. And yet, why is this student alone, why is she the only one with a specific geographic location, and why does she have no voice in a testimonial quote? Again, it seems that in pictures of study abroad, white students are everywhere, and students of color, if they are pictured at all, only appear in limited spaces within the study abroad structure.

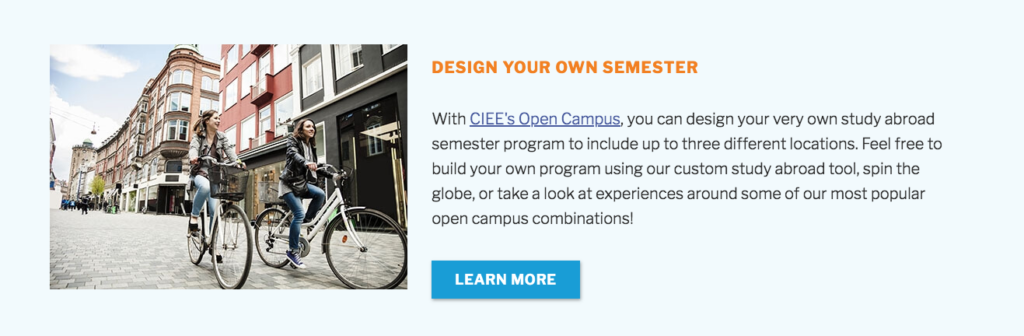

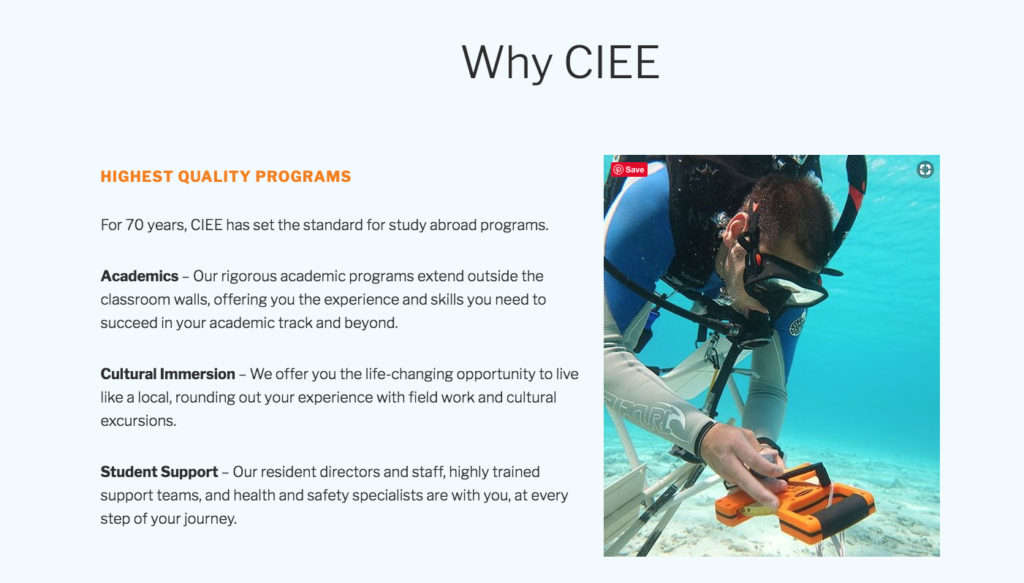

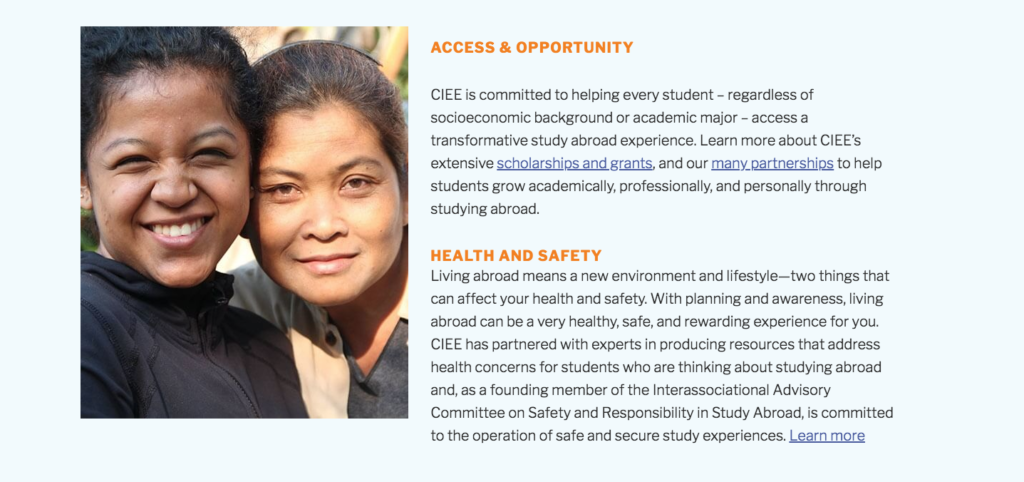

Scrolling down further (past more tourism photos) we see more evidence of this. White students bicycling and scuba diving are pictured next to titles like “design your own semester” and “highest quality programs”. Students of color appear next to “access & opportunity”. Scrolling further, we get a silhoutted person on a camel, and white students with an elephant (want orientalism/colonialism much?) and then the pictures end.

So overall, what do we see in these pages? White students having adventures, with students of color inserted as needing access and going to specific locations. Meanwhile, the language and intercultural skills they have acquired at home (and that a white student like me for example would need to rely more on study abroad for) are erased, even though there is research demonstrating they build upon these skills to expand their linguistic and intercultural knowledge abroad. Yes, this is only one website, but take a look at some more—what do you see?

Furthermore, this is the website of a program that is in fact trying to address this issue, and is putting real resources to it (and again, financial support is a major barrier that cannot be ignored). If these problems are this apparent when we are trying to help, what about when we are not? If we want to address the very real problem of the underrepresentation of racially minoritized students in U.S. study abroad, we need to be able to see just how white it is, and how we uphold this culture of whiteness in our representations and expectations of study abroad. Yes, this is uncomfortable for those of us who are white and were raised with colorblind ideologies, but we can’t fix problems that we won’t admit exist and don’t understand how we perpetuate.

Once we are aware of the problem, there are lots of things that can be done, as the other speakers in the colloquium pointed out, including hiring faculty of color on study abroad programs, representing students of color in study abroad, connecting them to experiences and locations abroad they find culturally relevant, listening to their experiences and not expecting them to be like those of white students, and having returning students of color interact with potentially interested students (again, check out their work!).

So, what do you see in our representations of study abroad? If (like me) you work in this field, as a researcher, practitioner, or participant, what will you do to shift these representations?

(Hands image from stokpic on pixabay, rest screenshotted from linked pages)

Comments

2 responses to “The Whiteness of U.S. Study Abroad”

Thoughtful, accurate and well presented. I’m sure you can imagine how study abroad programs were back in the early 1960’s when I was in college. Your efforts will make the world a better place: not just for ‘racially minoritized students," but for countries that tend toward xenophobia.

Thanks for including me with those who receive your blog. Marion

Thank you for reading!