It’s time for a new post on ideologies of study abroad! This series started last Spring, with a post on study abroad as tourism, and continued in September with one on study abroad as language immersion. In this post, I’ll be taking on study abroad as personal transformation, another commonly perceived outcome of study abroad.

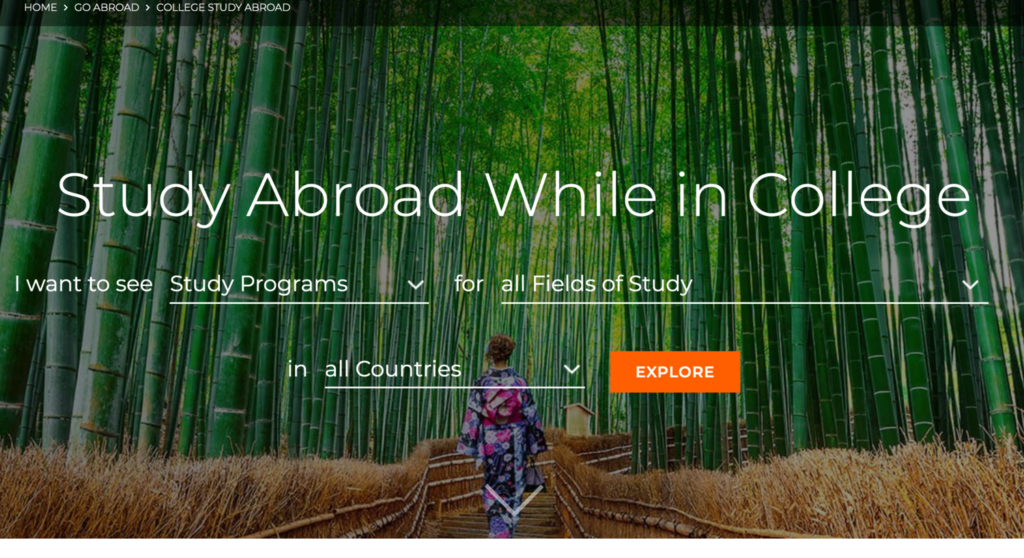

The ideology of study abroad as personal transformation focuses on “adventures” in “foreign” lands as a “life-changing” experience leading to personal growth. In narratives of study abroad, the focus is generally on how students overcome various obstacles, such as “culture shock” or logistical challenges to emerge with new perspectives, skills, and life experiences. In promotional materials, the transformative nature of study abroad is often represented through pictures that foreground and highground study abroad students against cityscapes or natural expanses, or alternatively engaging in risky adventures such as white-water rafting or ziplining. Two examples of this from prominent study abroad providers are shown below (this post is not meant to critique these providers specifically, as these examples are common in study abroad programming). On the IES website, the student is perched above a blurred cityscape, with the invitation to “Start your Adventure with IES Abroad”. In the second picture, students are enticed to explore CIEE programming against the backdrop of a student walking into a bamboo forest, clothed in traditional-looking garments.

In both cases, the focus of the photograph is the student themselves, with the local context a backdrop for their transformation and adventures. Local people are notably absent, although sometimes they do appear in the backgrounds of these photos, or with the students, but in ways that distinguish them from the study abroad student (e.g. race or traditional dress).

While personal transformation is certainly a positive goal, this particularly framing of it (part of the photographic “brand” of study abroad) is highly problematic in its reproduction of global power inequities. In general, the context of U.S. study abroad is one of predominantly White students from higher socio-economic classes traveling from a globally dominant country to less globally dominant ones (especially as U.S. study abroad expands beyond traditional destinations). This power differential is further emphasized when the local people and context are presented as a backdrop for the students’ personal transformation, and can be considered a colonial perspective–rather than extracting natural resources or labor for the empire, they are extraciting transformative experiences (which frequently may require local labor or resources). In certain cases, these transformative experiences can overlap with voluntouristic White saviourism, actively harming local contexts and people.

This focus on personal transformation during study abroad also minimizes other types of experiences. First, there are students who are not able to overcome obstacles abroad, or mold their experience into one of personal transformation. This can correlate with racialized or gendered experiences abroad, and discounting these experiences ignores the ways in which patriarchy and White supremacy shape these experiences. Similarly, the emphasis on study abroad for personal transformation ignores the potential for transformative experiences among students who are unable to study abroad. Overrepresenting the transformative experiences of predominantly White study abroad students from higher socioeconomic classes helps reproduce the racial and social hierarchies of U.S. society.

While I don’t think programs, students, and researchers who emphasize personal transformation are looking to actively reproduce colonial patterns and racial hierarchies, I think it is crucial to be aware of how this happens anyway. What would it look like to shift the brand of study abroad? To show students in the background learning from local communities? To recognize the transformative experiences of students who learn through their lived experiences in minoritized communities at home?

Leave a Reply